Why induction is not the foundation of science

A video recently circulated on X in which François Jacob said non-hypothesis-driven research is "very boring".

😯 François Jacob (co-discoverer of gene regulation) asked by Lucy Shapiro (Stanford):

— Itai Yanai (@ItaiYanai) November 24, 2023

"It's always been hypothesis-driven research [..] but a new way is looking at vast amounts of data and not asking a question, just seeing if it give you a pattern."

Jacob: "It’s very boring.." pic.twitter.com/mPJIp6xIfS

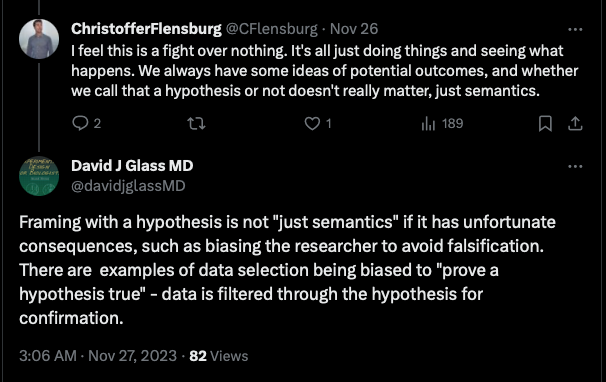

This provoked a response from many scientists, including Dr. David Glass. Chief amongst Davids claims was that induction is the “foundation of science”. I disagree with this claim for several reasons, and i'll discuss them here.

I hope my criticism of these ideas helps clarify why induction is not the basis of experimental science. We must adopt an experimental framework that is consistent with the true aim of science – explanation.

The main critique of hypothesis testing is that guessing the outcomes of experiments causes bias. Instead of hypothesizing, Newton suggests that we should just wait for the evidence.

One of the most famous quotes of all time: Isaac Newton's "Hypotheses Non Fingo" (I don't make hypotheses). He was asked to explain the cause of gravity, for which he had no data. So he pointed out that one should never guess, but wait for experimental evidence.

— David J Glass MD (@davidjglassMD) November 27, 2023

Newton's advice raises questions: How long should we wait, exactly? And where do we look for said evidence?

Experiments are planned activities, where we put a theory to the test. Science progresses by us putting forward explanatory theories that we think will solve gaps in our knowledge. These theories are bold guesses – they are conjectural. And they are integral to the scientific process.

In the absence of a working hypothesis, what on earth would the point of an experiment be?

Dr. Glass also claimed that it is ok for us to theorize, so long as hypotheses are abandoned in favor of questions when we execute experiments.

This seems farcical. It's erroneous to suggest that theory can guide our experiments but simply be disregarded to avoid bias in data interpretation. And no data can be understood without invoking a significant explanatory framework anyway.

Newtons advice insinuates that we can derive knowledge from observations, in a process called inductive reasoning, of which David is an advocate. This method suggests that scientific progress is made by making general conclusions from a set of specific observations. It assumes that observed patterns will extend to unobserved instances.

Yet induction is a seriously flawed method of scientific reasoning. I’ll outline two of its main limitations here.

Inductive reasoning is still the most useful framework for doing science - one seeks to learn from past experience (data) to make predictions about what will happen in the future (via repetition or generalization to other systems).... which can also be though of as model-testing.

— David J Glass MD (@davidjglassMD) November 27, 2023

First, induction cannot be logically justified.

Philosopher David Hume realized that the future does not necessarily resemble the past. To argue otherwise would be circular.

This means that we can't justify the truth of theories (e.g., “all swans are white”) from the truth of basic statements verified by experience (e.g., “all swans in my local park are white”).

How then do we justify any conclusions beyond past instances of which we have had experience?

The answer is that we simply can’t. There are no criteria at our disposal to establish the absolute truth of a theory.

But we can validly assert the falsity of a theory by observation; if i observe one black swan, it refutes the theory that all swans are white. Our ability to disprove theories by statements verified by experience is why falsifiability is key for scientific progress. And it is falsifiability which the hypothesis framework, and its underlying philosophy of critical rationalism, hinges upon.

Another limitation of induction is that it views prediction as the main aim of science.

The inductivists goal is to forecast the outcomes of future experiments off the back of repeated observations. This focus on predictability is odd. Being able to predict the outcome of an observation is not the same as understanding it. The latter depends on having a good explanation.

Our best scientific theories explain the very reality underlying our observations, whilst also containing accurate predictions. But "theories" produced by induction don't take this form.

Pursuing prediction is misguided, but there is more. The act of predicting the results of experiments, and extrapolating these findings, demands prior explanatory theories. How else could we account for the uncertainty in things we haven't observed? From this, it's obvious why Popper described induction as an illusion.

I'll end by granting David that our choice of experimental framing matters. It guides our scientific practice.

But it's induction that poses a greater threat to science than critical rationalism.

Scientists working under the guise of induction are encouraged to verify – rather than falsify – their predictions, whilst shielding their inexplicit theories from criticism. This is not conducive to knowledge growth.

Fortunately, we have an alternative: the hypothesis framework and its philosophy of critical rationalism. It can be summarized as boldly proposing new theories, trying our very best to disprove them, and only cautiously accepting those that survive our most severe criticism.